In August, my daughter, husband and I visited The Loris Malaguzzi International Centre in Reggio Emilia in Italy. The visit was extremely inspiring and thought-provoking – one of the best trips I have ever made.

Back in 2014 when I completed my teacher training at Bath Spa University, I was placed in a nursery school heavily inspired by the ‘Reggio Approach’. At the time, we had an amazing artist in residence, Pete Moorhouse, who worked on a range of creative projects with the children including woodwork, sculptures and visual arts. I remember Pete telling us about his study course in Reggio and ever since hearing about it and reading books at university, I have had a desire to visit.

The Loris Malaguzzi Centre in Reggio Emilia is open to the public and free of charge – something I was not aware of. I always thought the ateliers (art studios), were only part of a study course available to practitioners. Luckily for us, anyone can explore them, take photos and be in awe of their beauty. The week-long study course sounds and looks incredible, and certainly would be essential for any teacher wanting to fully understand this approach to teaching. A brief visit to the centre is unlikely to teach you the philosophy that underpins this remarkable way of seeing, appreciating and living and breathing the ‘Reggio way’.

This is only a snapshot reflection of my visit to the centre and contains my thoughts and opinions – it does not reflect the beliefs and philosophy of Reggio. For those that are interested to learn more about the centre or approach, I urge you to visit the Reggio Children website where you can find everything you need, including links to upcoming training groups and study materials.

Beauty, beauty everywhere

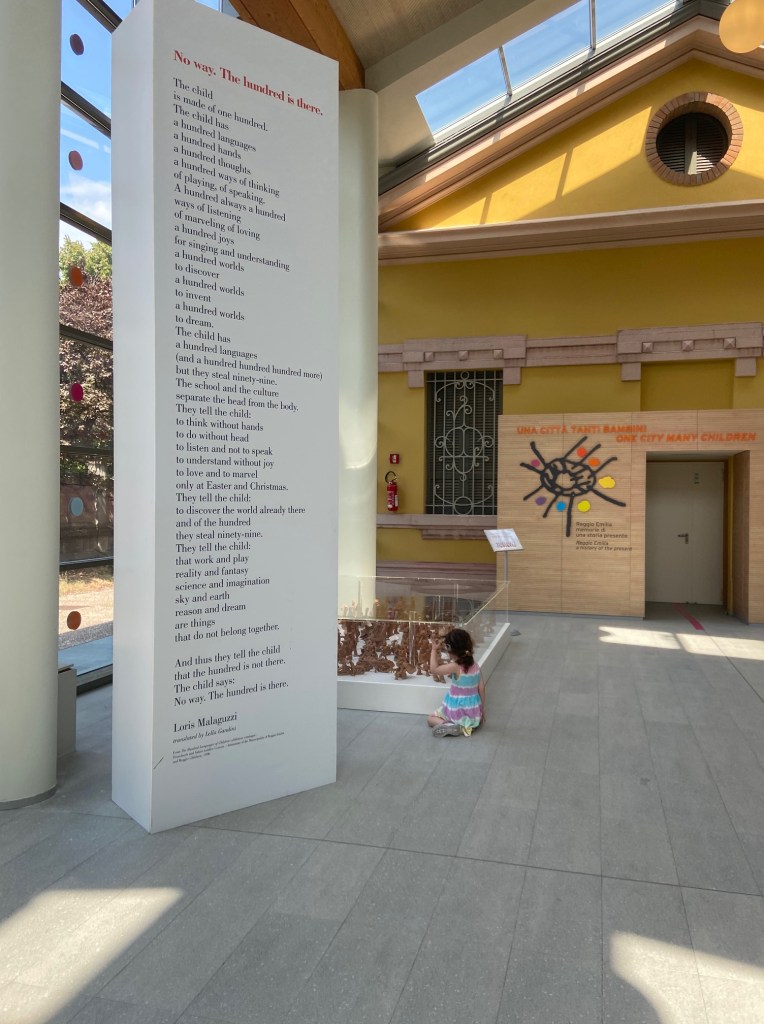

From the moment you enter the centre, you can’t help but notice how clean, fresh and light the building is – free from clutter or overwhelming décor. It makes you wonder whether the designers behind the physical space felt strongly about creating a space extremely inviting and calm, from the moment you step into the door. The building is a learning centre, a place of research, with many spaces for visitors to stop and reflect. There are reading materials everywhere and children’s artwork neatly presented to observe and admire.

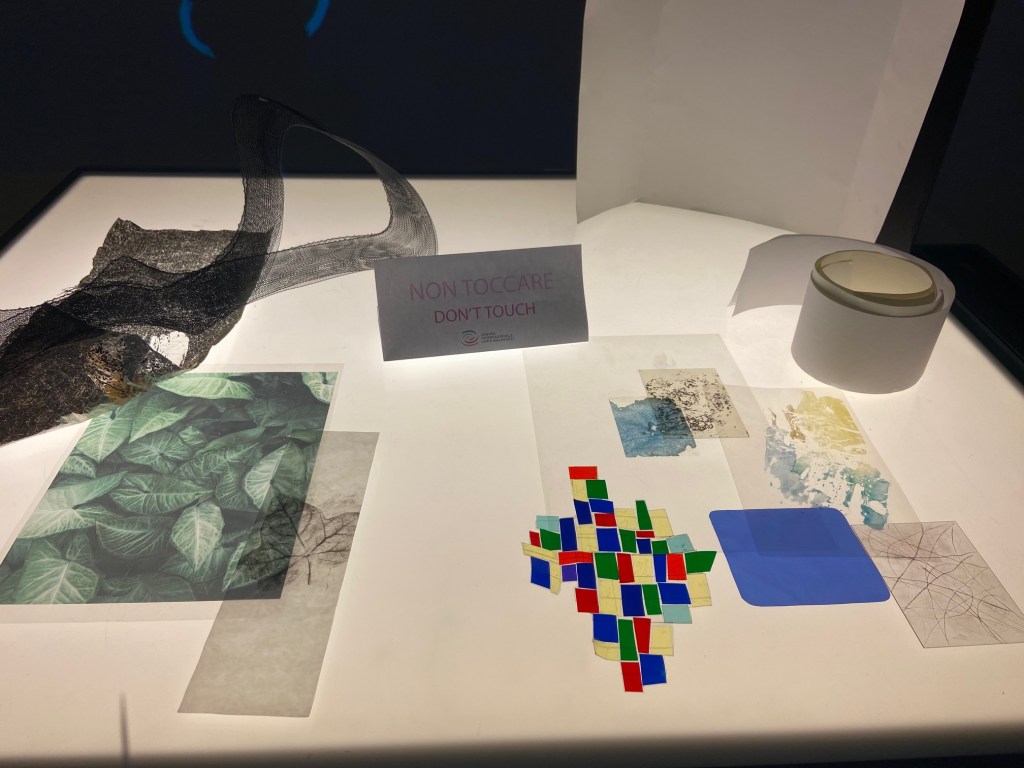

We grabbed a map from the help desk and started our adventure via an exciting corridor in the ‘Digital Landscapes’ atelier. The natural light faded and we entered a space full of bendy desk lamps, coloured and reflective materials, as well as cameras for producing digital images. This was the first time I had witnessed the way in which materials were presented at the centre, and I was captivated by its beauty and structured organisation.

The objects seemed to have been placed purposely in collections all over the tables: objects that are shiny/reflective, transparent objects in a variety of forms, textures of different materials and colours etc. On first glance it might feel overwhelming: how on earth can you choose one thing to focus on when there are hundreds of items in front of me? But I think that is the intention: practitioners want you to stop, pause and really look.

What do you notice? What does this make you think of or feel? How could we use this material in multiple ways?

Our modern world is full of surges of social media, and life can seem fast-paced as a result. In general, we give ourselves little time to ponder and delve deeper into our observations and thoughts.

At our creative sessions at Awe & Wonder, I think we have started to explore this way of looking and close observation. By setting out a range of interesting objects in a beautiful manner, with lots of free time to explore (something teachers in mainstream schools may not have enough of), children and adults are given the freedom to expand their ideas and come up with new ways of seeing and doing things.

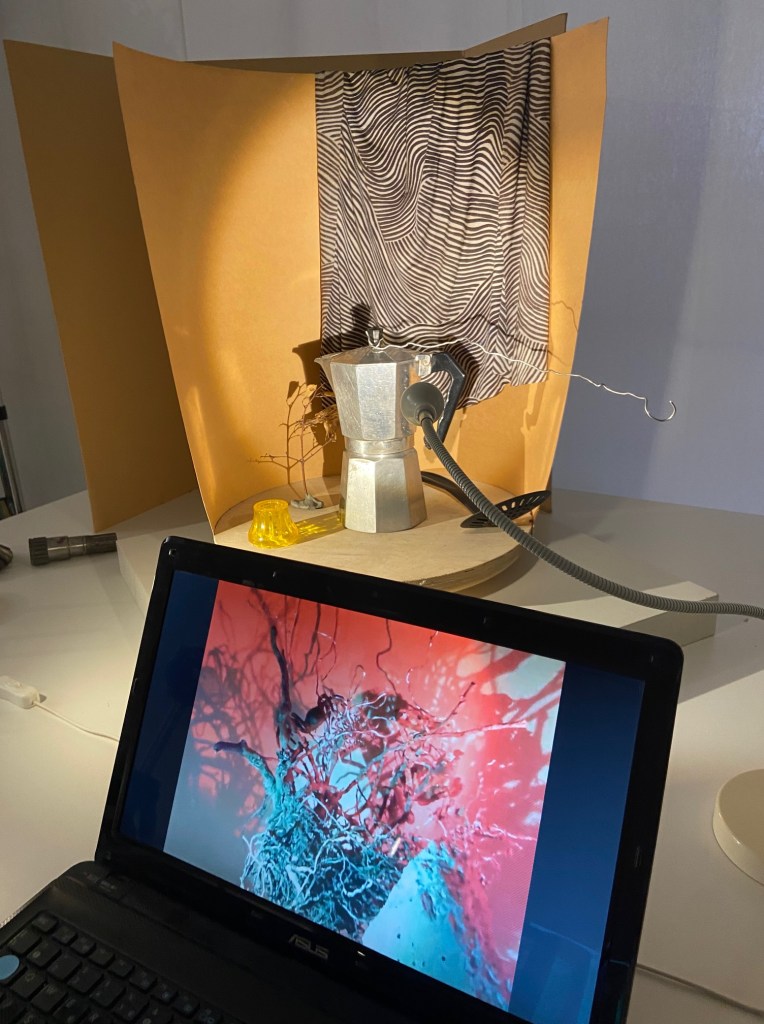

Moving through into the atelier, the beauty and magic continues. On one side of the studio there were large tubes and geometric shapes placed around the space, with digital images projected onto it. My daughter and I gasped with excitement seeing the rays of colour and light across the room.

Humans are naturally drawn towards light and shadows – there is something so magical and mesmerising about them. We often feature an overhead projector during our creative sessions for families to explore. However at Reggio, they take this exploration further by giving children autonomy to create their own digital landscapes to project onto objects via the use of technology and artistic software. On reflection, this is something that I would like to learn more about, and find out how/if we can introduce this element into my teaching, where children can use laptops and cameras to make real time imaginary worlds.

Organisation

I do not think it is possible to visit the Loris Malaguzzi Centre and not comment on the organisation and presentation – across the whole building. Even the cafeteria and bookshop are light, airy and beautiful.

Wandering around the ateliers, it is remarkable to observe the way items are colour coded and organised on every table or shelving unit. There is something so aesthetically pleasing seeing pieces of everyday plastic found in our everyday lives, sitting amongst other pieces of a varying shade, flowing into a rainbow effect of colour exploration.

The way in which objects are organised and presented makes me wonder about the reasons behind this: is it to inspire children to find multiple ways of seeing or doing things, to use our imaginations to create something unknown or new, is it to inspire us to notice similarities and differences between objects, or is it just to notice something beautiful or interesting?

My visit to the centre has made me question the resources I have acquired over the years and stored in my garage, in the hope that it ‘might be useful one day…’. If I can allow myself some time to sort and categorise items into colours or textures, I believe we could replicate some of this type of organisation and presentation at our creative sessions. Children deserve beautiful spaces to explore, and I think taking the time to invest in good organisation may bear fruit in the explorations children can experience.

Depth of Thinking and Learning

Imagine being given a piece of clay for the first time – you might poke it, rub it, realise it makes a mark on your hand, you might even make something with it – a ball, snake or sausage… Or you might not even want to touch it – some children hate the cold, earthy smell and texture of it. Imagine exploring clay once and the adult putting it away and saying, ‘Yep, well that’s clay’. You might want to explore it again, make another ball or an even longer snake, or you might not. At Reggio, it seems like they take their teachers and children on the deepest level possible of the exploration and thinking of clay.

Among the endless tools for mark making in clay, there were shelves upon shelves of clay in multiple forms – different shades of dried clay, in different gradients and colours. It is interesting to observe the centre describing ‘experimentations’ within clay – a little sign said ‘The relationship with objects that leave traces, that engrave and memorize the passage, the relationship, objects that let themselves be traversed by the clay, objects that become tools to produce and reproduce serial forms to modulate and modify’.

The centre seems to shine a light onto the depth of learning in early child development in every corner – encouraging us to stop, look deeper and really think about what is happening and the endless possibilities in learning and experience. In my teaching practice, I find this task sometimes quite difficult – maybe this is because I am constantly thinking about what I need to teach them, and because there could be 30 children in the class who all need to be meeting the same learning expectations, and worrying about the time I have left until I need to teach my next input. Who is this for? Do some teachers feel like this because of external pressures and workload? What if we were all given the space, time, freedom to observe children at our own pace? What if we were given the autonomy to decide what children should be learning, the materials they could explore and play with, instead of following a planned curriculum or syllabus. What if we were able to be fully present with the children, capture their actions, voice and then go on a natural journey of learning full of curiosity and wonder – without the need to stop the learning for a whole class input such as phonics or writing? In an ideal world, I think most teachers want to work in this way, but I wonder if it is simply not practical with large classes and a set curriculum.

The right to explore the environment is pure and visible during our Awe and Wonder sessions. Children and their caregivers are free to wonder around the pop-up art studio for two whole hours, taking their time and switching between creative stations as they come and go. As an artist educator and parent, this is where I feel the most liberated. It is also a space where I have seen some of the deepest learning happen, where children are free to test out ideas, revisit experiences, build upon prior learning, explore new social interactions, and resolve conflicts (not that I have seen many). Play, as outlined in this video, is one of the ways we can strengthen opportunities for an array of learning and help children and adults to thrive. The importance of play on wellbeing and child development seems to be well researched and documented, which makes me wonder how ‘play’ takes a role within mainstream school settings, and throughout local communities.

This position paper written by the Division of Educational and Child Psychology is a useful short read about play, especially in relation to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. When I began putting together the project proposal for Awe and Wonder, I used children’s rights as a starting point: asking local councillors how we were upholding these rights within the local community. If a child has little exposure to ‘creative play’ activities at home, where can they explore this within the town that they live in? This might look different for children living in areas where they have access to large museums or galleries that hold events throughout the year, but for children living in small villages, or in areas of poverty or deprivation, the opportunities might be limited. It is also useful to discuss that even if a child is born into an area full of creative possibilities and opportunities, their caregiver may not have the confidence, time or motivation to take their child to the museum or gallery? I have heard from many families about the struggle to take part in creative activities in the home, many saying that they dislike ‘the mess’, or they ‘just don’t know what to set out, or what to do’. If we have spaces in our community for families to come together to ‘play’, we remove those barriers and children and caregivers could potentially thrive collectively.

The Hundred Languages of Children

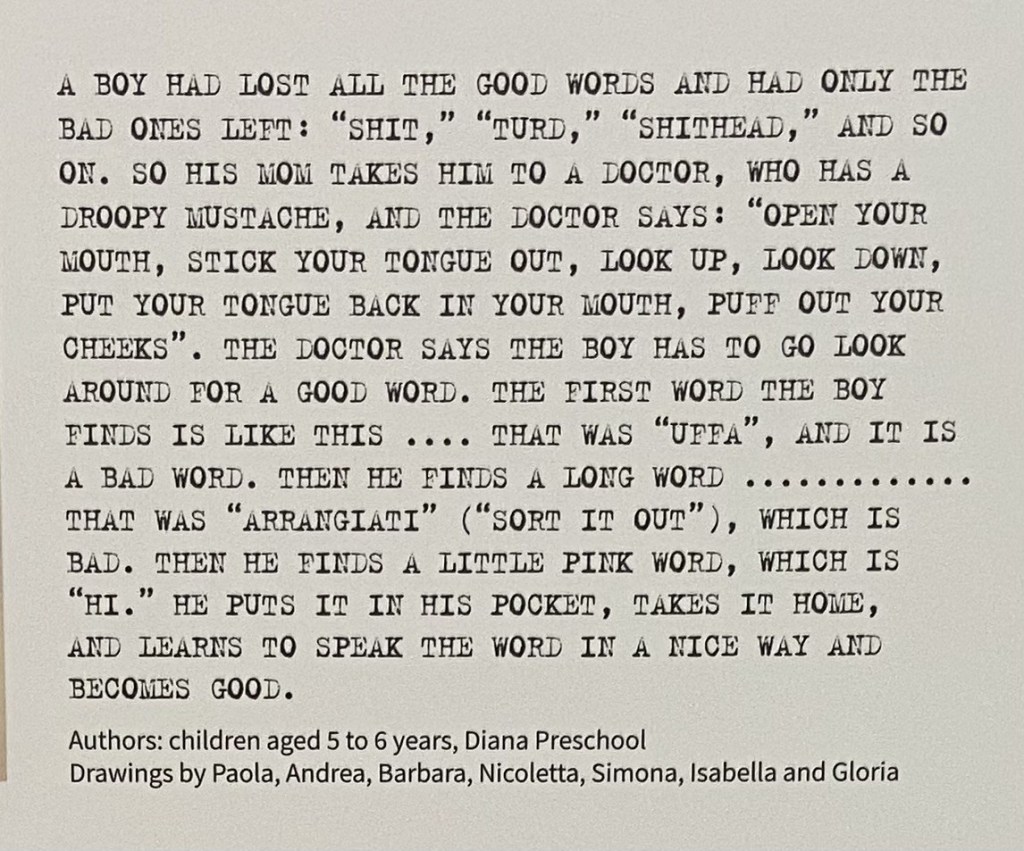

Downstairs, past the digital landscapes atelier, we found an exhibition room dedicated to children’s storytelling. I have always felt passionate about creating opportunities for children to share their own narratives and creative imaginations. During my teaching practice, I’ve taken time to listen to children’s stories, and dictate them word for word, recording them in a little book. These stories would then be shared amongst the class (and to parents/caregivers) on a taped out stage – often known as ‘Helicopter Stories’ by Trisha Lee, hugely inspired by the teachings of Vivian Gussin Paley. Listening to children’s ‘stories in their head’ allows us to get to know the child on a deeper level, find out their interests, loved family members, friends and fascinations. It also allows children to become storytellers, without the need for writing a story or following a prompt.

At the Loris Malaguzzi Centre they presented many stories and illustrations from children from schools in Reggio. One that I particularly enjoyed was the following story, written by a group of 5 and 6 year-olds from the Diana Preschool:

This example demonstrates to me the appreciation and respect the teachers have for the learning of children – ask yourself, if this group of children had invented this story in your school setting, would you proudly share it to the teaching team, and/or the wider community? Would you display in within your class walls or corridor displays? Or would you shy away from it, not even scribe it at all due to its ‘foul language’? Listening to this story, I can just imagine Loris Malaguzzi smiling in awe of the pure humour and playfulness coming through the words.

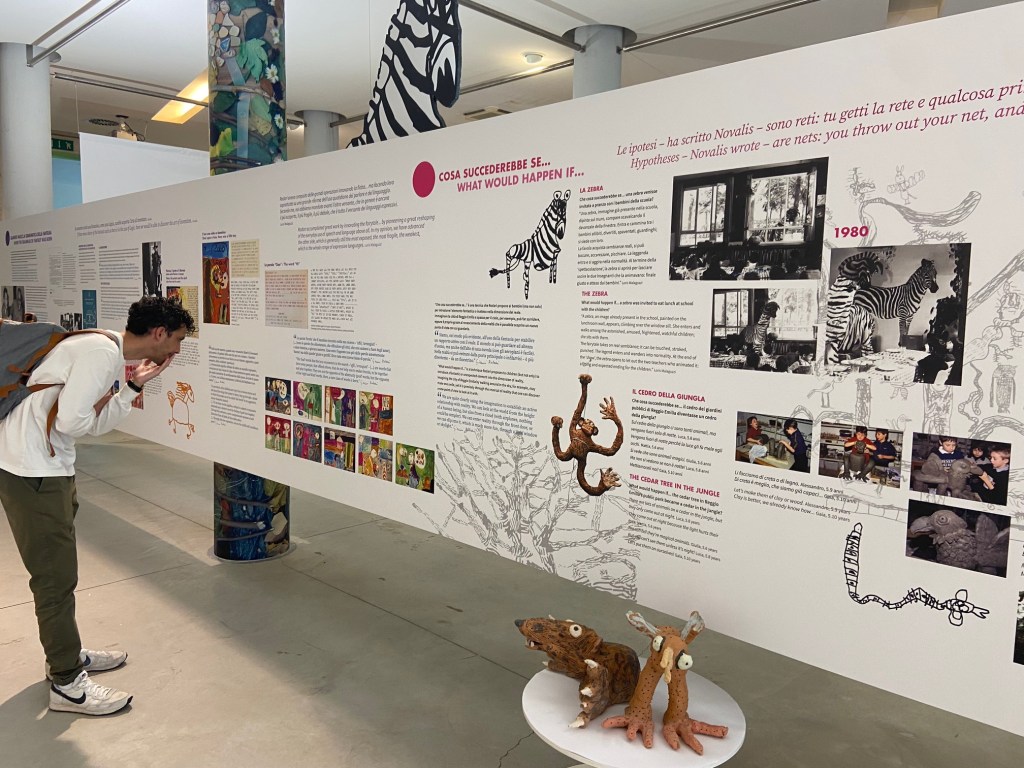

I also really liked reading about journalist and writer Gianni Rodari and his work with some of the Reggio schools. The exhibition display states: whilst playing alongside children, he would often use the phrase, ‘What would happen if…?” inviting children to step into an exciting imaginary world of interesting scenarios. Around the exhibition there are countless photos and stories captured from the children, each unique and individual. I love working in this way as it poses no right or wrong answers, every child is free to express their ideas in their own way without any limitations.

If you head upstairs in the centre, you will find a large warehouse full of exhibits for you to admire and be inspired by. My favourite part of the room was the clay sculptures made by the 4-6 year olds, which are not only a testament to their creativity but also a reflection of their imaginative processes. The supporting documentation available teaches us about the thinking behind their explorations, offering valuable insights into the minds of these young artists. It’s fascinating to see how these children translate their thoughts and feelings into physical form. The sculptures are simply beautiful, showcasing such detail and intricate design, each piece telling its own unique story. There is so much to learn from this display, and it really needs further study and appreciation, as it encourages viewers of all ages to appreciate the raw, unfiltered expression of art and the profoundness that can emerge from the innocence of childhood creativity.

Following this visit, the main areas to explore in my practice are:

- How we display provocations – looking through the lens of a child, what possibilities lie ahead?

- Less is more, how can I organise materials better?

- What technology can we bring into our sessions and what experiences does this offer children?

- How can we go deeper with our thinking and learning about materials or experiences? How can we document this/share this with our families?

Thank you to the Loris Malaguzzi International Centre for opening its doors to the general public and giving us a small insight into your unique way of seeing and appreciating children. I would like to close this reflection with a poem from Loris Malaguzzi (translated by Lella Gandini), which was displayed in the centre next to an array of clay figures made from children.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.

A hundred always a hundred

ways of listening

of marveling of loving

a hundred joys

for singing and understanding

a hundred worlds

to discover

a hundred worlds

to invent

a hundred worlds

to dream.

The child has

a hundred languages

(and a hundred hundred hundred more)

but they steal ninety-nine.

The school and the culture

separate the head from the body.

They tell the child:

to think without hands

to do without head

to listen and not to speak

to understand without joy

to love and to marvel

only at Easter and Christmas.

They tell the child:

to discover the world already there

and of the hundred

they steal ninety-nine.

They tell the child:

that work and play

reality and fantasy

science and imagination

sky and earth

reason and dream

are things

that do not belong together.

And thus they tell the child

that the hundred is not there.

The child says:

No way. The hundred is there.

This blog post has been written by Artist Educator Victoria Deelchand-Bee who runs Awe & Wonder creative play sessions for families living in and around Crewkerne, Somerset. If you would like to learn more about what we do, send us a message or find us on Facebook and Instagram.

Leave a comment